They Were Here First

My friend Keith lives in Bedford, on property that’s been in his family for generations. Over the years, he’s seen turkeys, coyotes, foxes, and of course a million deer. But when he went outside one night recently and spotted a large, hulking shadow behind his house, he thought his eyes must be playing tricks on him. Experience told him that nothing in his neighborhood could be that big.

But then he turned on his phone’s flashlight and found out that you can’t always trust experience. The shadow resolved into a large Black Bear, the first he’d ever seen there. It lumbered away at once, leaving unanswered the question of whose heart was beating faster.

Keith is far from the only Westchester County resident to encounter a bear so close to home. In just the past year, reports of wandering Black Bears have come in from Chappaqua, New Castle, Armonk, and other nearby towns.

And it’s not just Westchester, but across New York, the Northeast, and much of North America. Just recently in California, for example, a Lake Tahoe family, having been bothered for months by mysterious “snoring” noises inside their house, finally discovered the cause: a mother bear and her four yearling cubs who’d spent the winter snoozing in the basement!

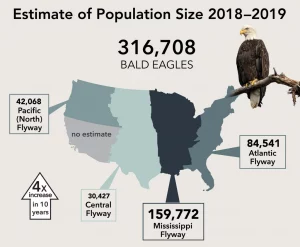

If it seems like bears are popping up—or ambling around—nearly everywhere these days, that’s because they are. Black Bear populations have grown significantly in recent decades across North America, and experts estimate that as many as 900,000 bears inhabit the United States and Canada. In many areas, there are now three or four times as many bears as there were just forty years ago…and while nearly a million chipmunks or squirrels might be able to stay hidden, the same isn’t true for creatures that can stand six feet tall and reach 600 or more pounds in weight.

Why are there so many more bears today? The answer reveals a rare environmental success story involving—as so many such stories do—us humans changing the way we act to the benefit of the creatures we share the land with.

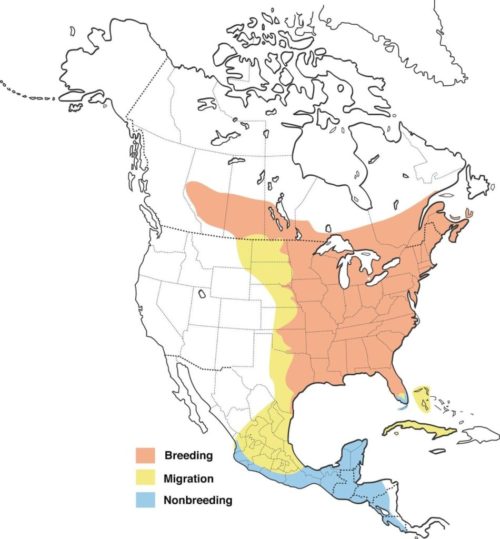

Before Europeans arrived, the Northeastern landscape was largely forested. Indigenous people cleared trees only modestly, and both their villages and cultivation were designed to avoid making major changes in the environment. They and Black Bears, which relied on undisturbed woodlands, were able to coexist.

The colonists, however, clearcut the forests both for lumber and to make room for dairy and other farms. By the mid-19th century only about a quarter of the Northeast’s original forest cover remained, and populations of bears, deer, and countless other species were vanishing along with the trees. If these circumstances had continued, the Black Bear would likely have become extinct across large parts of its range.

Fortunately, things changed just in time. With the building of the railroads and the availability of seemingly unlimited fertile land in the Midwest and beyond, vast swathes of Northeastern farmland were abandoned. Over the decades, these fields and pastures were gradually reclaimed by forest, and populations of Black Bears and other animals rebounded as well.

Humans also took a more active role to protect the species. For centuries, Black Bears were freely shot for their meat, fat, and fur, and because they were considered a nuisance or danger. Starting in the early 20th century, though, a series of laws were passed to regulate bear hunting in New York, and most other states as well.

Today, the combination of healthy bear numbers and the building of new houses and condos in previously forested land has made human-bear interactions inevitable. Also inevitable: That when they do happen, we’ll all hear about it on the local news and social media.

Even with the rising number of encounters, the number of bear attacks on humans remains extremely low. But they do occur: Since 1900, roughly one person has been attacked by a Black Bear somewhere in the United States each year, with a death resulting about every other year. Those numbers are both likely to rise. So, despite the low risk, given that bears’ size and strength, and the fact that females with cubs can be notoriously testy, it’s best to know what to do if you come face-to-face with one.

Most importantly, be alert and use your common sense. Try to spot a bear when you’re still a healthy distance away—and then don’t run towards it waving your camera because you want to post a great pic on Instagram. If one does seem interested or aggressive, don’t run away, either: Stand your ground, make yourself seem bigger by waving your arms, and make a lot of noise. The bear is extremely likely to depart as fast as it can in the other direction.

For a deeper dive, here’s a useful rundown from the Humane Society:

But all the good advice on earth goes out the window if, like Keith, you simply step out your own back door and find a bear standing there. It’s far better to try to avoid this heart-thumping experience entirely, which you can do with a little smart planning.

Nearly all wandering Black Bears fall into one of two categories: young, newly independent individuals looking for territories of their own and adult males on the hunt for mates. Since neither mates nor territory are likely to exist in your backyard, the bears will want to pass through as quickly as possible—unless, of course, you invite them to stay for dinner.

To a bear, birdseed and suet in feeders, poorly maintained compost bins, haphazardly covered garbage cans, and the aromas and food scraps from a barbecue grill all have the appeal of an all-night diner to a hungry traveler. So it’s best to take a few precautions and make sure your diner is closed to any bears that may wander through.

I think it’s a very hopeful sign for the future that Black Bears and other predators (including Coywolves, Bobcats, and Red Foxes) are surviving—and even thriving—in this crowded region. But, like every wild creature in the world we’ve made, bears depend on us to understand what they need and what they don’t. Through our actions, we’ll decide if our two species will continue to coexist peacefully, or if we’ll again drive these magnificent creatures off the land they inhabited long before we got here.

by Joseph Wallace

Copyright © 2022

![broad-billed-hummingbird-melton Broad-billed hummingbird (male) in Arizona. [click image for more Arizona butterflies and photo credit.]](https://www.blog.sawmillriveraudubon.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/broad-billed-hummingbird-melton-1024x708-300x207.jpg)