Teenager Season

From an amateur naturalist’s point of view, Croton Point Park isn’t at its best right now. The weather’s been hot and steamy (when it hasn’t been pouring); the RV lot, campground, and picnic areas have been jam-packed; and many of the birds, done with nesting, have fallen silent. Some have even left the park to begin their long journey south for the winter.

Even so, in some ways this is one of my favorite times to visit Croton Point. Why? Because it’s teenager season. No, I’m not talking about human teenagers (though there are plenty of them around these days), but about teenage birds. They’re all over! Wherever I look, I seem to see another young Robin, Catbird, or Song Sparrow landing on a branch or hopping across the grass.

How do you know when you’re seeing a young bird? Look closely and you’ll see that, just like human adolescents, they’re clumsy and unkempt. Their feathers are patchy, their movements uncertain. Sometimes they haven’t even grown a tail yet.

Another way to tell: If you watch for a minute, you may spot a parent bird or two somewhere near these awkward youngsters. And then you’ll notice that the adults look harassed, stressed, overworked.

Of course they do. They’re dealing with the scary challenges that parents of any species face as their children step into the wider world: Trying to protect them, teach them, and encourage them to be independent, all at the same time.

And time is short to accomplish all these tasks. Familiar species like Yellow Warblers, Baltimore Orioles, Bobolinks, and many others winter as far away as South America. They don’t arrive here until late April or May, and from the moment they touch down the clock is already ticking down to their departure south, which can start as early as late July.

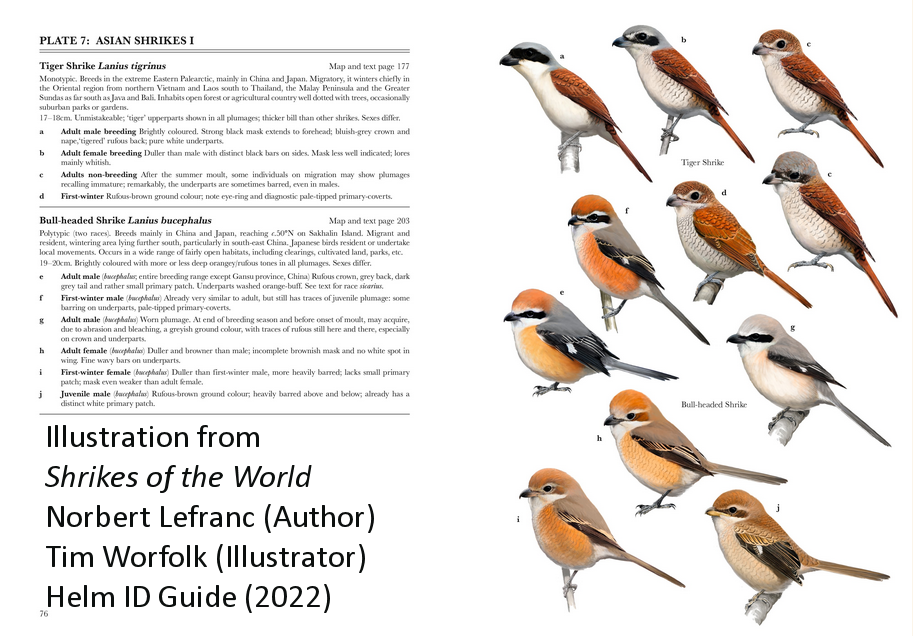

Bobolink Flock

And they have a lot to do in that brief window: They have to pair up (very few songbirds mate for life), build a nest, produce and brood eggs, and tend to the helpless new chicks. By the time hatchlings are ready to leave the nest, there may be only a few weeks left before migration begins…and there’s plenty for the young birds to learn before they start their first long journey to their wintering grounds.

The instinct to migrate and some other crucial aspects of bird behavior—such as flying—are inborn, carried in the birds’ genes. But many other behaviors are learned. For example, in a process similar to our own, most songbirds learn their species’ language (their songs) by memorizing what the adults around them are saying. (Usually—again like human children—as they practice what they’ve heard, they’ll add variations to make it their own.)

Birds (mostly males but some females, too) have to know how to sing to establish and keep a territory, to attract a mate, and to bond with their mates. Singing is essential for the continuation of the species. But other learned behaviors are equally essential for a bird’s survival: Knowing what to eat (and what not to) and how to get hold of enough of it to survive.

Fledgling Blue Jays

That’s where the parent birds come in. Most of us have seen patchy young birds sitting on the ground or a branch, begging to be fed. Just as they did in the nest, they’ll call pathetically, flap their threadbare wings, and even chase their harried-looking parents around until the adult gives in and deposits a bug or seed into their gaping maws.

But even as they beg, teenage birds are also observing. Researchers studying Blue Jays, for example, have found that young birds carefully watch as their parents and other flock mates hunt for caterpillars, which to a jay can be either delicious and nutritious or prickly and toxic. Only by paying attention can the youngsters learn to avoid eating the wrong caterpillar and suffering unpleasant—and possibly dangerous—after-effects.

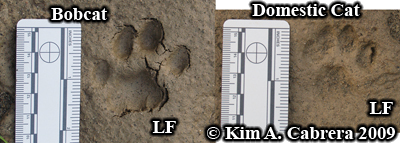

Young birds learning what to eat from their elders is a well-known behavior. Twice at Croton Point in recent weeks, though, I’ve witnessed something that seems much less thoroughly studied: Parent birds teaching their offspring how not to be eaten.

Crows mobbing a hawk

Both times, my attention was first caught by loud, strident alarm calls, the kind little birds make when they’re mobbing a predator like a hawk, owl, or snake. Many songbirds will make loud, far-carrying raspy sounds, while others, like Chickadees (an angry “Chick-a-dee-dee-dee-dee!”) sound their own distinctive alarms.

Regardless of the call, though, it always has the same meaning. Songbirds will come together to harass a predator (a behavior known as “mobbing”) for two connected reasons: To chase away the threat while simultaneously announcing to every bird within earshot, “There’s danger here!”

At Croton Point, the alarms were aimed at Red-tailed Hawks. Both times, the hawk was being harassed by at least a dozen different songbirds of several different species, including Baltimore and Orchard Orioles, Robins, Mockingbirds, Chickadees, and Titmice. And each time the mobs featured both adult birds and young ones who’d recently left the nest.

Baltimore Oriole and Red-tailed Hawk

I always enjoy watching songbird mobbing behavior. (It’s fun to see the underbird win out over the Big Bad for once.) Except one thing stuck out this time: At Croton Point Park, at least, these songbirds don’t usually mob the resident Red-tailed Hawks. They ignore them.

The reason for this typical unconcern seems simple: Although they do sometimes hunt birds (usually larger ones), Red-tails eat mostly good-sized mammals such as rabbits, squirrels, and voles. They’re not much of a threat to a little Chickadee or Titmouse, certainly not worthy of a large mob.

So what was going on here? Just another sign of the parent birds’ stress over being responsible for offspring that had only recently left the nest?

I don’t think it’s anthropomorphic to say that that was surely part of it. But to me it seemed like something else as well. I think that the grown-up birds were modeling crucial behavior for their young. “Big birds that look like this can hurt you,” they seemed to be saying. “But here’s something you can do that will help keep you safe.”

And, as a parent, an uncle, and a teacher and mentor to high-school students in the area, I got it. I really did. After all, isn’t this what we all hope to teach the vulnerable—and so often heedless—young people in our lives?

Copyright © 2023 by Joseph Wallace