The Season of Comings and Goings

Recently my wife and I took an early morning walk in Croton Point Park. Again and again we were reminded that, while most of us humans remain stuck near home, for countless birds this is peak season for arrivals and departures.

Some of the species that were familiar sights in the park all spring and summer—such as the Purple Martins that raised their young in the condos near the front entrance—are have long since headed off to warmer climes. Others that we think of as year-round residents—like Black-capped Chickadees and Common Grackles—are still here, but with an unexpected wrinkle: Most are not the same individuals we saw all summer, having arrived from further north while “ours” have flown south.

Meanwhile, the group of birds known as passage migrants—species that neither breed nor winter here, including most warblers, vireos, and shorebirds—continue to stop off to rest and feed before resuming their own journeys south. And a handful of fascinating species that merely winter in our region (like the Lapland Longspur, which nests in the High Arctic) have also started to arrive.

Because so many migrating birds are small and garbed in drab fall plumage, they can be easy to miss. But any observant visitor to Croton Point is nearly guaranteed to spot perhaps our most spectacular recent arrivals: birds of prey, which seem to be overflowing the park these days.

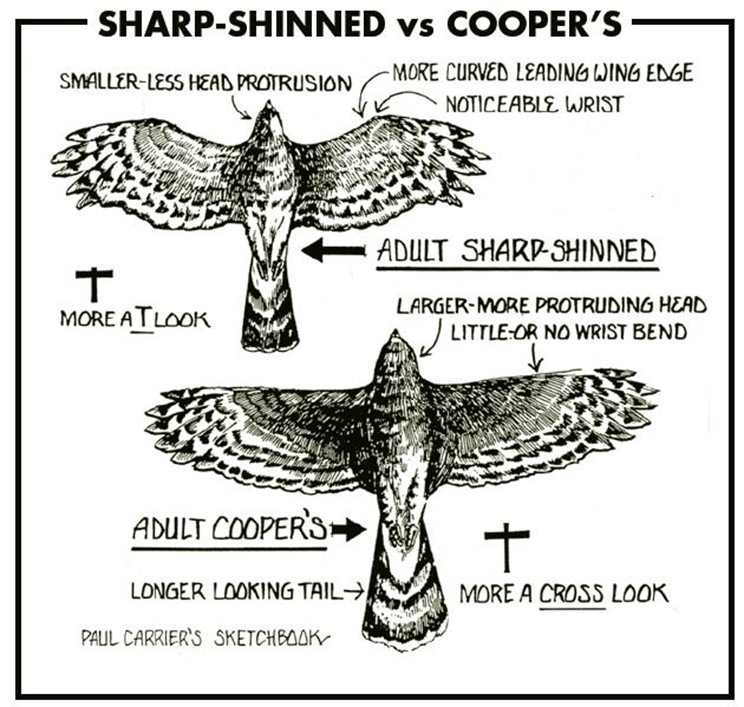

On our recent walk, we were lucky enough to get good looks at two closely related hawks from the group known as accipiters: the tiny Sharp-shinned and larger Cooper’s Hawks. Be careful with the ID, though: A large female Sharp-shin isn’t much different in size from a small male Cooper’s, and they also share comparatively short, broad wings and long, banded tails.

As is true for most Northeastern raptors, populations of these handsome hawks crashed by the 1970s due to DDT use, but they have since recovered spectacularly. Both species thrive in suburban woodlots, where they hunt smaller birds. (They can even take up long-term residence near bird feeders, putting pressure on local songbird populations.)

On our walk, we watched a Cooper’s Hawk chase—and be chased by—another regular denizen of the park these days: a Northern Harrier. This distinctive raptor (look for the long wings held in a “V” shape, prominent white patch on its rump, and roundish, owl-like face) makes for a memorable sight as it quarters low over the hill.

Photo: Jeffery Seneca

The Harrier is considered threatened In New York State. As so often, the main threat to the species is habitat loss, in this case the filling of marshes and conversion of unmowed grasslands to other uses.

Other frequently seen species in the park are clearly not threatened in our area…but they were not that long ago. Famously, for example, both Ospreys and Bald Eagles also saw their populations crash due to DDT, to the extent that by the 1970s some scientists thought they might go extinct in the Northeast.

Of course, that’s not what happened. The banning of DDT, careful protection, the cleaning up of the Hudson River, the building of nest platforms for Ospreys and, especially, New York’s Bald Eagle reintroduction program all bringing both species back in spectacular fashion. Even a short visit in the fall will usually feature at least one Osprey, often carrying a fish as it stokes up for its southward journey. And late fall through winter is prime season for eagle-spotting, as birds from further north move down this way in search of open water.

Surprisingly, the most spectacular sightings during our walk didn’t involve huge, showy birds like the eagle or Osprey, but one of the region’s smallest raptors: the American Kestrel. In little more than an hour, we saw more than a dozen of these slender, fierce little falcons, many of which are stopping off en route to the southern U.S. or Central America.

At one point at least half a dozen Kestrels rose into the air at once to dive-bomb a passing Cooper’s Hawk. To see so many birds of prey in a single moment was stunning and heartening.

American Kestrels remain one of the most common raptors in the United States, with a population estimated at 4 million individuals. However, this is also a species in rapid decline, populations having decreased by at least 50% nationwide in recent decades.

One challenge for any efforts to slow the Kestrel’s decline: No one can be sure exactly what’s causing it. Most likely, it’s a combination of factors: habitat loss that results in fewer places to hunt; overuse of neonicotinoids and other pesticides; plummeting populations of grasshoppers and other large insects, which are among the Kestrel’s main food sources; and competition from European Starlings, House Sparrows, and other species for a dwindling number of nesting cavities.

The view of so many different raptor species, ranging from tiny to huge, during a single walk feels like an unexpected gift. But it’s one that also demands we think more deeply about the inextricable ways our birds’ fates depend on the choices we humans make, both now and in the future. And, just as crucially, how vital it is that places like Croton Point Park remain refuges for raptors—among so many other birds—during this time of comings and goings, and always.