The River in Winter

A skim of new ice in a calm inlet. A scattering of Bufflehead ducks, each shining like a black-and-white beacon amid the river’s silvery swells. Six Bald Eagles—no, eight—soaring and tumbling in the sky above the whitecaps.

These are among the highlights of a morning walk in Croton Point Park at this season. What they—and so much else, seen and unseen—all share is the presence of the Hudson River, which dominates not only the landscape but much of the cycle of life in our region.

What makes our area’s stretch of river such a haven? A variety of factors, chief among them water temperature. As near as Albany, the Hudson’s temperature has fallen to about 37 degrees. But the waters in and around Haverstraw Bay currently remain in the high 40s, a vitally important difference to many species seeking food and shelter during the coldest months.

Buffleheads, a common winter visitor in the bay and surrounding waters, are among my favorite birds. Their name—supposedly drawn from the fact that their heads, bulky for their size, resemble those of bison—is fun to say out loud. Their eye-catching pattern makes for a striking contrast against the silvery winter river. (In good light, the “black” on their heads and neck shines with beautiful purple-green iridescence). And the way they play peekaboo, disappearing instantly beneath the surface in dives that can last for many seconds, seems like a magic trick.

But perhaps the most appealing thing about Buffleheads is how intrepid they are. These tiny ducks are only about half the length of the Mallard and weigh little more than a pound, yet they are undeterred by the frigid air and icy waters where they make their winter homes.

They do grant one concession to the weather: They’re rarely seen on the open ocean, instead congregating in protected bays and rivers and near the coast. Here they find the snails and crustaceans that make up most of their winter diet.

We may never witness this around here, but it’s always fascinating to learn what “our” visiting birds are doing in other seasons. Buffleheads, for example, have evolved a fascinating breeding strategy on their nesting grounds to our north.

Unlike most ducks, they do not nest on the ground. Instead, they choose preexisting tree cavities, relying almost exclusively on holes originally excavated by Northern Flickers. Thus Bufflehead populations are dependent on birds they otherwise have little connection with…and on forestry practices that leave dead and dying trees standing.

While Bald Eagles are glamorous and easily identifiable, they are far from the only raptor you can see in this region during winter. (Red-tailed Hawks and the smaller Sharp-shinned and Coopers Hawks are fairly common, while several other species make rarer appearances.) But eagles stand out: They are so huge—and their population growth since the 1970s so spectacular—that even non-birders take notice.

Fifty years ago, eagles had virtually vanished from the Northeast. Among the culprits were habitat destruction and pollution of the lakes and rivers the birds depended on for food. Most notoriously, though, pesticides (chiefly DDT) caused female eagles to lay eggs with thin, fragile shells, causing nesting failures that persisted for year after year.

Only when the birds were nearly gone did aggressive recovery efforts get underway. The banning of DDT, coupled with an aggressive reintroduction program using birds from healthier populations to the north and west, eventually reversed the decline and led to a new eagle population boom. Today, more than 100 pairs nest in the Hudson Valley, and even more visit in the winter.

In all seasons, the river is what attracts Bald Eagles to this region. As the winter comes on, and rivers and lakes further north start to ice over, the open waters of Haverstraw Bay (where the Hudson is at its widest) and to its south serve as a magnet for the region’s eagles.

During especially cold snaps, ice floes float up and down the Hudson with the tides. At these times, you can look out over the river—especially between Peekskill and the Tappan Zee Bridge—and see dozens of eagles either riding the floes or riding the air currents above them.

Not every creature that takes advantage of the river is as attention-grabbing as the Bald Eagle. During the warmer months, for example, the turbid waters and abundant vegetation of Haverstraw Bay provide a haven for young Striped Bass, among many other fish species. In the winter, though, while these young fish move south to New York Harbor, adult stripers congregate in the bay, where they find the water temperatures and salinity levels they prefer.

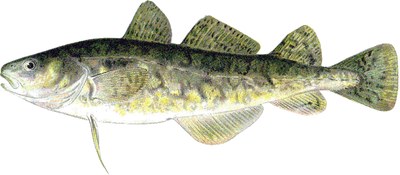

A less spectacular fish found in the bay at this season is the Atlantic tomcod. This is a species that thrives in cold water (its nicknames include “frostfish” and “winter cod”) and lives as far north as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and northern Newfoundland. Their mid- to late-winter spawning runs often take place under ice-covered waters.

Perhaps the most unexpected fact about tomcod involves the species’ response to General Electric’s dumping of PCBs into the river between the 1940s and 1970s. While this ongoing release of toxic chemicals had a disastrous and long-lasting effect on other species, the tomcod survived…and even thrived.

The cause of this unusual success: Rapid-fire evolution in action. A small number of tomcod had a rare genetic mutation that provided resistance to PCBs. Via natural selection, the mutation quickly spread throughout the river’s tomcod population. In recent years, scientists have found that the mutation now occurs in 99% of all Hudson River tomcod, compared to only 10% of those found in other waters.

Unfortunately, not all threats to the tomcod have been overcome by evolution. This species relies on cold waters, and with the warming of the river due to climate change, the tomcod’s Hudson River spawning runs have diminished significantly in recent years.

Climate change is just one of the continuing threats to the health of the river and its inhabitants. Deforestation, pesticide and fertilizer runoff, and other effects of the nearby—and ever-growing—human population also pose ongoing challenges.

Other threats to the river’s denizens remain more mysterious. As local vultures—and anyone walking along the river in recent weeks—can tell you, a large die-off of Atlantic menhaden (also commonly called bunker) has been taking place in Northeastern waters—not only in the Hudson River, but all the way from Cape Cod to South Carolina.

New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) is studying potential causes, but as of this writing has not released its conclusions. Scientists in Connecticut, however, have pointed to a recent bunker population boom as a factor. A boom, in fact, that is a direct reflection of the increased health of our inshore waters, thanks to more stringent regulation of commercial fishing limits and pollutants.

One result of these regulations: So many millions of bunker massing in our waters this fall that some were caught by dropping temperatures and dwindling food supplies before migrating south to warmer climes. The die-off, researchers point out, may seem dramatic to those onshore, but actually encompasses a minuscule fraction of an increasingly healthy fish population. New York’s DEC will soon confirm whether the Hudson River die-off can be attributed to the same causes.

Whatever the reasons prove to be, however, the menhaden die-off serves as a reminder that the river may dominate our landscape, but we still dominate the river. And that our responsibility to protect and manage it, and the creatures that rely on it, is a challenge for all seasons.

By Joseph Wallace

Copyright © 2020