If You Plant It

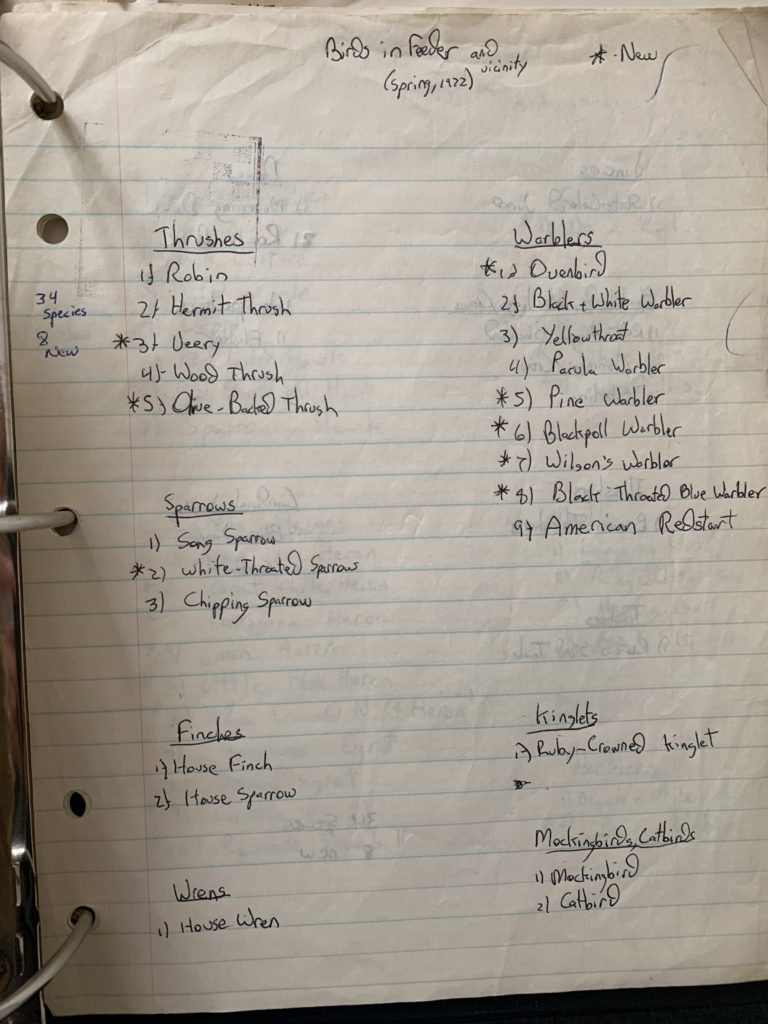

Many years ago, as a child in Midwood, Brooklyn, I decided to set up a sunflower-seed feeder (in reality just a tin-foil tray hanging on our magnolia tree) in our postage-stamp backyard. Every day after school I’d check to see if it had attracted anything beyond the usual sparrows, House Finches, and Grackles.

Photo: Joe Wallace.

I didn’t hold out much hope—after all, ours was just a tiny patch of green in an enormous city—but, amazingly, it worked.Soon less familiar birds began showing up in the feeder and surrounding bushes, including some my Peterson informed me didn’t even eat seeds. One day it might be an American Redstart fluttering amid the magnolia leaves, the next a Brown Thrasher staring at me from the lilac. A Black-throated Blue Warbler, a Wood Thrush, a pair of Baltimore Orioles.

Watching these unexpected visitors, I began to see something about migration that I’d never truly understood before. I knew that the passage of birds each spring was like a great river flowing overhead…a river I couldn’t really see or hear. Yet somehow the birds streaming past could see me, or at least my yard—even my homemade feeder. They’d noticed.

This precious memory came rushing back to me this past weekend, as my wife and I walked over the top of the mostly shorn grassland hill in Croton Point Park. (It’s undergoing an important restoration to eradicate encroaching invasives and replace them with native grasses and other bird-and pollinator- friendly native vegetation.)

This site didn’t always host 100 acres of grassland, of course. Not that long ago it was a toxic landfill, a Superfund site that took years and countless millions of dollars to clean up. Now capped, it has been transformed into the kind of habitat that has long been under intense pressure across the country. (It’s easy to see how grasslands are good candidates for tilled fields, monoculture crops, harsh fertilizers and pesticides. As a result, this kind of native habitat has vanished in many areas and is besieged in most others.)

There’s plenty of green in Westchester…but there aren’t many grasslands, wild meadows, or unmowed fields. Migrating birds that rely on such specialized ecosystems have long since kept on flying as they search for the habitat they need. And yet they were keeping an eye out, ready to notice if anything changed and to take advantage of it.

Photo: Frank Shufelt.

It didn’t take long. Nearly as soon as the dump was capped and grasses were planted on the hill, the grassland birds began to appear…some only rarely seen in Westchester County for many years. On our recent walk there, we spotted at least seven Eastern Meadowlarks, their odd, stuttering flight making them easy to identify even before we raised our binoculars. A group of five Horned Larks foraged across the newly turned earth. A flock of American Pipits pinwheeled past, letting loose with their sweet flight notes.

In spring and summer, the hill echoes with the bubbling song of nesting Bobolinks and the insect-like buzz of Grasshopper Sparrows. And all seasons bring an array of raptors that have noticed the increase in prey species: American Kestrels, Red-shouldered and Cooper’s Hawks, Northern Harriers and others. (Some years have even seen Short-eared Owls, a diurnal hunter that could be seen quartering the hilltop on silent wings.)

The connection between this expansive grassland and my tiny Brooklyn yard made me think about something else: Not every important environmental effort needs to be on a scale as grand as the reclamation of the Croton Point grassland. Even little actions can have an outsize impact, just as my filling a tinfoil tray with seed did at a time and place where few people set up bird feeders.

Here’s one example: We can replace the non-native plants that fill most of our gardens (and are useless as food sources to most birds and insects) with native species. Even a small patch, winterberry instead of flame (aka burning) bush, butterfly weed in place of tulips, can make a real difference. (More on the growing “Pollinator Pathway” movement, which spearheads such efforts, can be found in this article from Teatown Reservation and many other online sources: https://www.teatown.org/pollinator-pathways/.

Whether on Croton Point or in our own backyards, we can all use the heartening reminder: If you plant it, if you provide that food, safety, welcome, the birds will come. As they pass by in that great river every spring and fall, they’re always keeping an eye out, and they’ll notice.

I’m certain of this, because the beautiful, unexpected visitors to my Brooklyn backyard so many years ago showed me.

Joe Wallace