Here Be Dragons

Once, when I was very young—and already fascinated by the natural world around me—I plucked a Japanese beetle off a bush and took a closer look. As it marched across my palm, I inspected its gleaming brown wing cases, their iridescence flashing in the sun.

Then I tossed beetle into the air above my head, watching to see it unfold its wings and fly off. Before it could, though, something shaped like a tiny fighter jet came darting into view. As I watched, the intruder snatched the beetle out of the air and carried it off.

The predator was, of course, a dragonfly. A big green one—a Green Darner, I discovered later. I was immediately fascinated by both its grace and its snatch-and-grab hunting technique, but not until much later did I discover how remarkable dragonflies and their cousins, the damselflies (Order Odonata, called “odonates” as a group), truly are. (You can distinguish the two because dragonflies’ wings are fixed roughly perpendicular to their bodies, while damselflies’ wings fold.)

First I learned how many dragonfly and damselfly species exist. With new ones still being discovered, more than 6000 species have been identified worldwide (they’re native to every continent save Antarctica) and around 200 in New York State alone. The largest known species (Megaloprepus caerulatus, a damselfly whose wings whirl like a helicopter’s rotors when it flies) has a wingspan of about 7.5 inches, while the wingspan of the smallest, the dragonfly Nannophya pygmaea, doesn’t even reach an inch.

And the common names! Unlike ornithologists, who tend to use plainly descriptive or habitat-oriented names (e.g., Black-Capped, Boreal, and Mountain Chickadees), entomologists have allowed the poetry in their souls to guide them. Thus we have been gifted with the Wandering Glider, Eastern Pondhawk, Halloween Pennant, Ebony Jewelwing, Blue Dasher, and many others.

These glorious names give only a hint of how colorful these insects are. And there’s so much more to marvel at: These small, ferocious predators lead extraordinary lives, the most vivid parts of which remain largely hidden from our view.

For example: Different species employ varying techniques to contend with cold northern winters. Most Green Darners, for example (along some other insects, most famously Monarch Butterflies) migrate to escape the cold weather. Like the vast majority of insects, though, nearly all temperate dragon- and damselflies spend their whole lives in the area where they were born, no matter the temperature.

Remarkably, though, unlike butterflies (which winter over as eggs, chrysalises, or adults in a kind of hibernation), the odonates remain active, feeding and growing all winter long…even during the coldest of cold snaps. The secret of their success is a stage of their life cycle that reads like science fiction.

Dragon- and damselflies are among the most aerial of all insects. They can barely walk (at most an awkward step or two), instead merely perching to rest. They hunt and mate on the wing, and many species even lay their eggs while flying. (If you’ve ever seen a dragonfly seeming to dip its “tail” repeatedly into a pond, that’s a female laying its eggs, often on or among leaves just below the water’s surface.)

Once the eggs hatch out, however, a mirror-image phase of the dragonfly’s life cycle begins: the nymphs not only cannot fly, but live an entirely aquatic existence, walking with ease and breathing through gill-like structures on their bodies. It is this phase that allows our northern species to stay active year-round—because, of course, even under a thick coating of ice, most ponds and lakes never fully freeze.

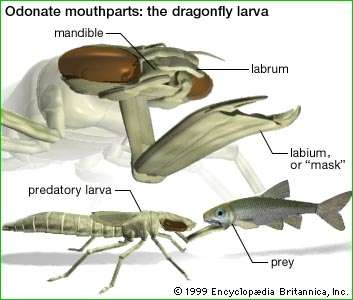

Nymphs (also called the larvae and, in some species, naiads) are even fiercer predators than the adults, and are especially skilled at ambush hunting. They come equipped with keen eyesight and strong, serrated mandibles, and many species have also evolved a powerful weapon to aid them in the hunt: a long, sharp, prehensile appendage called a labium.

When at rest, the labium folds up under the larva’s head and remains locked in place. But when potential prey—creatures as substantial as tadpoles and small fish for larger dragonfly species—comes within range, the labium unfolds and, driven by hydraulic pressure created by the nymph’s abdominal muscles, jabs forward at great speed.

In some species, the labium impales its prey. In others, pincers at its tip grasp the unwary target. Then the appendage draws back in towards the mandibles, providing the young dragonfly with its next meal.

Nymphs spend months—sometimes even years—underwater before emerging and transforming into winged adults. (Unlike butterflies, dragon- and damselflies skip the pupal stage and emerge fully formed through the nymph’s cracked-open skin. Inspect reeds and other emergent vegetation near waterline, and you may spot the nymph-shaped skins that have been left behind.)

So right now, even though it’s been months since we saw adult dragonflies zooming across the sky or damselflies fluttering amid the flowers, their nymphs are moving amid the fish, tadpoles, and other creatures in our ponds, preparing for the approaching spring…and the next stage in their fascinating and surprising lives.

Copyright © 2020 by Joseph Wallace