Quest Bird

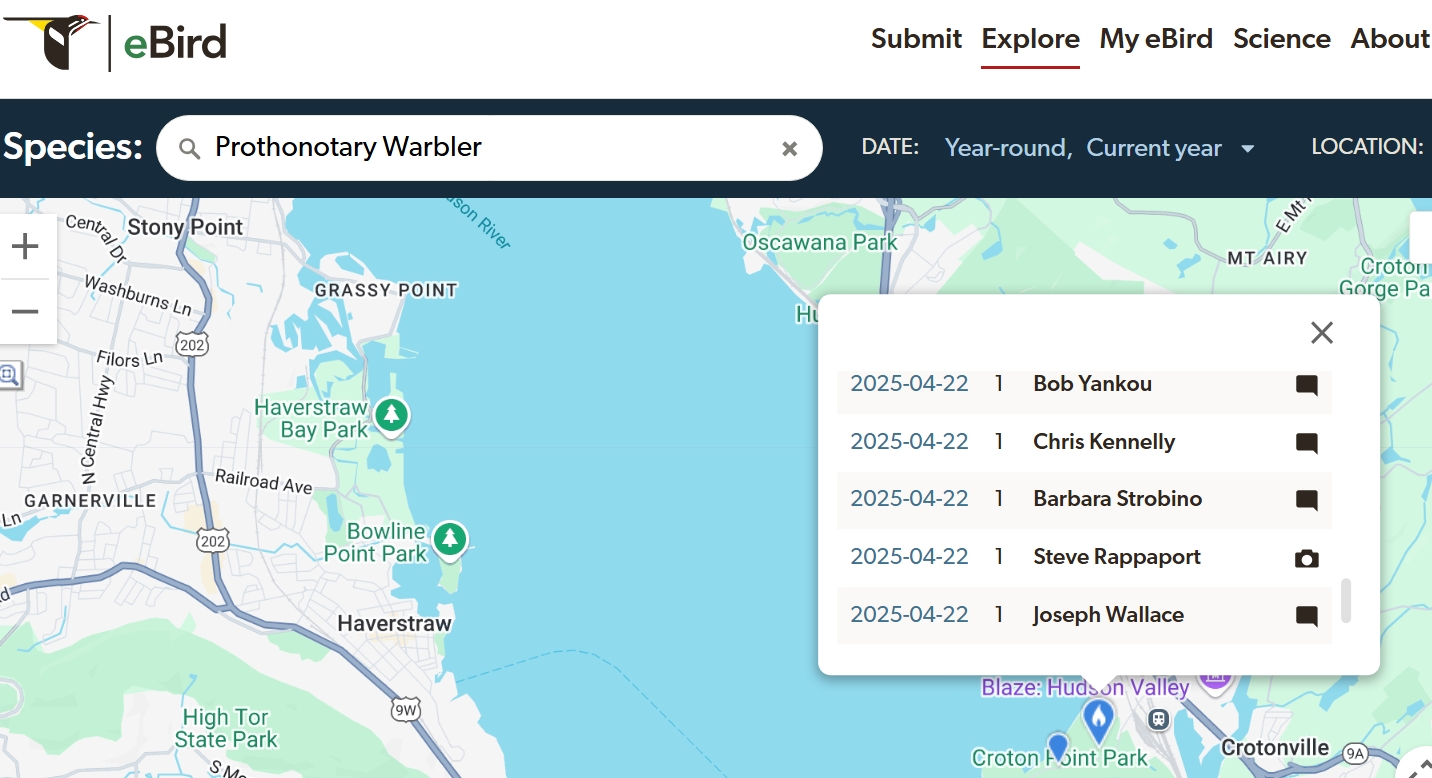

A friend of mine saw a rare and beautiful bird at a local park recently: a Prothonotary Warbler, a gorgeous species more typically seen in southern swamplands. Immediately, he did what most avid birders do these days when they spot a rarity: He got the word out.

What happened next had all the momentum of a viral ad campaign. News of the sighting spread on WhatsApp, Discord, and other chat channels, and birders flocked to the patch of woods where the warbler had been spotted. Throughout the day, the bird’s movements were reported in minute detail through precise directions and pins on Google Maps.

Because of all this concerted effort, at least a couple of dozen birders saw the Prothonotary who otherwise wouldn’t have. (Including me.)

The drawing power of this online grapevine is hard to overstate, especially when it comes to the greatest rarities. For instance, when a spectacular Steller’s Sea-Eagle, normally home in far-off Russia and Japan, visited New England and Maritime Canada a few years back, people came from all over the world to see it. And even less notable sightings can summon birders from other states and regions.

I’m a willing participant in the system, both reporting my own rarities and following others’ tips. Though I didn’t drive up to see the Sea-Eagle, rare-bird alerts and chats have allowed me to add several birds to my life list in recent years. These included a Red-flanked Bluetail, an Asian native that hung out for weeks in a New Jersey yard, which I almost certainly would never have seen otherwise.

But here’s the truth: A big part of me wishes the system had never been created. I know I’d see fewer new birds…but at the same time, it would be easier for me to recapture the sense of wonder I felt before Merlin, Discord, and pins in online maps existed. Back when I spent the summer in the Vermont wilderness with my friend Tom, when the natural world around us was filled with delicious mysteries.

I loved trying to solve those puzzles with nothing but my eyes, ears, binoculars, and old Peterson field guide. Every day I’d sit by an open window, birdsong pouring in from the woods all around as I wrote. Then, when it was time for a break, I’d go try out to discover who was making all that glorious hullabaloo.

Sometimes the answer was easy to learn. That staccato series of tooting sounds? A Black-billed Cuckoo climbing like a squirrel through the foliage. That joyful cry of “Whip! Three Cheers!”? (Or, as Tom called it, “Drink! Three Beers!”) A brazen Olive-sided Flycatcher. The science-fictiony series of notes coming from a nearby field? A Bobolink.

Other mysteries proved harder to crack. For example, one of the characteristic sounds in the woods around the cabin was a high-pitched, slightly buzzy song whose rhythm reminded me of the famous opening notes from Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

Unfortunately, the singer always remained hidden in the leafed-out canopy at the top of a tree. I’d crane my neck painfully, but I never got even a glimpse…until finally one day I figured out what to do. Finding a spot that gave me a good view of the treetops, I lay down on the damp ground amid the dead leaves and pine needles and peered upward, waiting for the singing bird to show itself.

Eventually Tom came over to see what I was doing. “You all right?” he asked.

“Just waiting for a bird,” I explained, never taking my eyes off the seemingly deserted treetop.

There was a long pause. Then I heard Tom said “Ohhh-kayyyy,” drawing out the syllables. And that was all. He already knew I was a hopeless case when it came to nature.

Finally, after I’d spent an eternity lying still while countless little forest critters crawled across my skin, the singer showed himself: A beautiful male Black-throated Green Warbler. As it turned out, that’s a species I’ve seen countless times since, including just this week. But I still get a little thrill whenever I spot one, remembering my hard-won triumph that day.

Another puzzle presented a different kind of challenge. While Tom and I were out fishing on the lake early one morning, we heard the strangest sound coming from the woods onshore. It was a muffled, low-pitched thumping, starting slowly and then building over about ten seconds to a rapid crescendo. I seemed to feel the vibrations as much in my bones as through my ears.

When the crescendo ended, leaving nothing but a kind of ringing silence, I looked at Tom. He smiled at my expression and said, “A Ruffed Grouse standing on a log and calling for a mate.” He shook his head, knowing what my next question would be. “They’re pretty hard to see. Very shy.”

He was right about that. We heard the drumming often (it’s actually produced by the grouse flapping its wings rapidly, as the accompanying video shows), but never caught even a glimpse until the day one attacked us.

No, really. We came around a bend in the trail and suddenly this large creature was hissing and charging across the ground directly at our legs. Afterwards, we both confessed that we’d thought we were being mugged by a porcupine—a highly unlikely yet bone-chilling concept. But no, it was a fully puffed-up female Ruffed Grouse, her little downy chicks clustering behind her as she rushed to defend them. In the end, she merely stood close by, glaring, as we edged away and out of sight.

Amazingly, though, my favorite bird from that magical time was one I never glimpsed, even though I spent all summer searching for it.

The Pileated Woodpecker.

Going into that summer, I’d never seen a Pileated (it was not a species likely to show up in Brooklyn), but the pictures in my field guide and nature magazines had always entranced me. A woodpecker the size of a crow, with a jet-black body, black-and-white-striped face, white patches on its wings in flight, and a brilliant red crest? Who wouldn’t want to see one?

And there were plenty of Pileated Woodpeckers in the Vermont woods around our cabin. We found the huge, blocky excavations they’d make in trees (and the piles of fresh woodchips they’d leave at the bases) throughout the forest. In what felt like a taunt, a Pileated even visited a dying pine tree a stone’s throw from the cabin, but only when we weren’t there. (The tree eventually gave up the ghost and fell over.)

Nor were the excavations the only evidence of the birds’ presence. I could hear the powerful drumming as they hammered at tree trunks in the distance, and at least twice I heard a wild, bugling call coming from deep in the woods, far out of reach.

I can only imagine how many times Pileated Woodpeckers saw me that summer, but it was a one-way relationship. And I knew why: Because the birds had decided that they didn’t want to be seen, not by me. And deep down I not only respected but admired that. After all, shouldn’t it have been their choice? They were the ones who truly called these woods home, while I was merely a visitor. An interloper.

Today, people would say that the Pileated Woodpecker was my nemesis bird. But back then its absence felt magical, even mythical, to me. And the search for it enlivened every walk in the woods I took.

Forget “nemesis.” It was my quest bird.

And my quest continued for more than a decade after my Vermont summer, sometimes in ways both amusing and frustrating. For example, for years after college my wife and I lived in Manhattan, and regularly I’d get calls from her father in Harrison in the Westchester suburbs reporting on his latest sighting.

Julian was so uninterested in wild birds that he called them all chickens, but Pileateds impressed even him. “I’m watching a chicken-chopper take apart a tree right now,” he’d tell me over the phone. “Want to come up and see it?”

And I confess that I’d give the idea some serious thought. (Okay, it’ll take me about half an hour on the subway to Grand Central. Then forty-five minutes on Metro North, ten minutes from the station to the bird… I wonder if it’ll still be there?)

But I never tilted at that windmill. And it was only years later, after we’d moved up to Westchester, before a Pileated finally decide to let me see it. There were no trumpets to herald the moment: Completely unconcerned as my wife and I walked past, it perched in plain view at close range, digging into a sawn-off tree stump.

In life the bird was spectacular, as I’d known it would be, and I was happy to finally add it to my list. Yet I wasn’t as thrilled as I’d expected to be to see my quest finally end. Instead, I was surprised to feel a vivid sense of loss, one that took a long time to fade.

In fact, I still feel this mix of happiness and sadness even today, when Pileated Woodpeckers sometimes visit my own little suburban backyard. Deep down, I think I’ll always miss the years when I was filled with anticipation because I might finally see my first one tomorrow. Or, if not then, the next day.

And that, I think, helps explain why I don’t love today’s methodical, almost clinical approach to finding and IDing special birds. What’s gained are more species for the list. What’s lost: The deeper thrill of solving the mystery for yourself, tied inextricably to the knowledge that you might never solve it at all. There’s a lot to be said for always living in suspense…and in hope.

So, when the first report of the Prothonotary Warbler pinged on my phone, I hurried over, gloried in its beauty, and passed the word along. But then, after a few minutes, I left the bird to others and walked away. Putting my phone back in my pocket, I spent the next couple of hours wandering alone in far corners of the park, simply watching and listening.

I didn’t solve all the mysteries I encountered that day, of course, just as I hadn’t during my summer in the wilderness. Nor would I want to, because to me that’s what makes quests both beautiful and poignant: They can last a day, or a lifetime.

Copyright © 2025 by Joseph Wallace