The Unseen Jungle

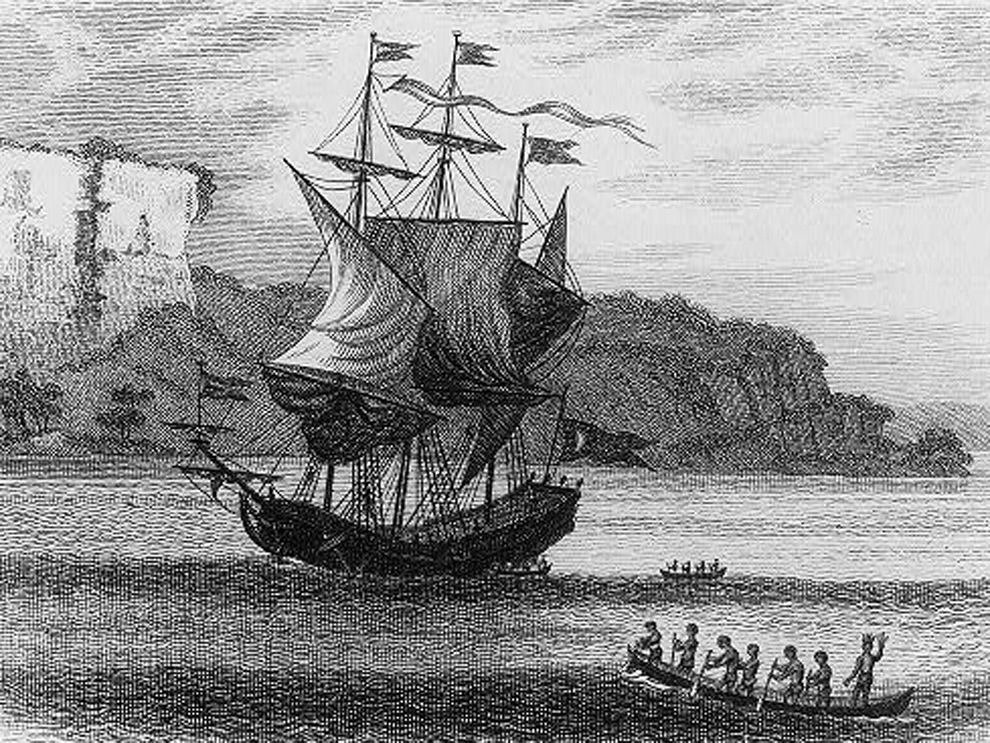

In 1609, Henry Hudson sailed his ship Half Moon from what would soon become New Amsterdam upriver in search of the Northwest Passage, supposed gateway to the riches of Asia. About 30 miles north, after the dramatic palisades along the shore softened into rolling hills, he came upon a stretch where the river broadened to more than three miles from shore to shore. He was certain he’d found his holy grail, which he immediately claimed for Holland.

Sorry, Henry. In his defense, Hudson was far from the first to let hopes outpace reality during explorations of the New World. But if he’d had thought to ask the local Native Americans who’d been plying this stretch of water since time immemorial, they would have told him that he’d “discovered” the passage to nowhere but hundreds of miles of more river.

Hudson was right about one thing, though: This, the widest point of the river’s estuary and now known as Haverstraw Bay, was—and is—something special, worthy of celebration if not of “claiming.” (Note: An estuary is a river’s tidal zone, where freshwater from upstream meets the ocean saltwater. Though estuaries are most often found near a river’s mouth, the tides flow—to a greater or lesser degree—into and out of the Hudson for more than 150 miles, all the way to the Federal Dam in Troy.)

As the Wappinger people, who occupied the east bank in this region, also could have told him, Haverstraw Bay—which stretches from Croton Point north for about six miles—is one of the most important habitats along the whole river. (It’s been designated as a “Significant Coastal Fish and Wildlife Habitat” by New York State.)

The bay plays a crucial role in the river ecosystem, and it all starts with its depth, tidal nature, and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. It’s rarely more than ten feet deep on its eastern side, and the tides carrying a regular influx of salt water into this shallow, often sunlit expanse help create a fertile brackish environment.

Such conditions, explains Tom Lake, Estuary Naturalist in the DEC [Department of Environmental Conservation] Hudson River Estuary Program, create an ideal nursery for young fish. “Unlike the clear water of the Atlantic,” he says, “Haverstraw Bay is generally turbid, off-color with suspended sediments, making it more difficult for predators to find smaller fish. Inch-long river herring in the open ocean would have a very short expected survival time.”

These conditions also help create a riotous growth of aquatic plants, which provide additional hiding places for young fish. It may be hard to imagine as you walk along the path at Croton Landing or look north from Croton Point Park, but it’s a jungle down there.

And, like all jungles, it plays host to a breathtaking variety and abundance of creatures—in this case, ranging from minuscule plankton to massive Atlantic sturgeon, which can weigh 800 pounds as adults. “Perhaps the key role of Haverstraw Bay,” says Lake, “is that it is a nursery area both for young-of-year fish [fish in the first year of their lives] from further upriver—such as striped bass and river herring—and young-of-year fish from the ocean, including bluefish and Atlantic menhaden.”

The symbol of the Hudson River estuary—the Atlantic sturgeon—provides a vivid example of the interlocking roles of Haverstraw Bay, the river, and the ocean beyond.

Sturgeon spawn in the river north of the bay, mainly from Hyde Park to Catskill. The young fish stay in the river for up to eight years, relying—like so many other species—on the bay for seasonal food and shelter. Then they head out to sea, where they spend most of their long lives (up to 60 years) in the ocean, only occasionally wandering in and out of other rivers from Canada to Georgia.

When males born in the Hudson River are about twelve years of age—and females close to twenty—they return to the Hudson to spawn. This drive to spawn where they themselves were born, shared with salmon and other diadromous fish, shows the ultimate importance of continuing to protect Haverstraw Bay, not only now but for future generations of fish and humans alike.

But the sturgeon and other famous Hudson River denizens—like striped bass, Atlantic shad, and alewives, currently migrating in vast numbers upriver to breed—are far from the only oceangoing fish that depend on Haverstraw Bay. In fact, some visitors over the past quarter century must have deeply startled their first human observers.

“In dry summers, the bay can reach near fifty percent salinity,” Tom Lake points out. “This intrusion of salty water can lure tropical species such as crevalle jack, lookdown, and even bonefish into the bay.” They’re joined by more northerly saltwater fish, including summer flounder, northern sennet (a kind of barracuda), and northern kingfish.

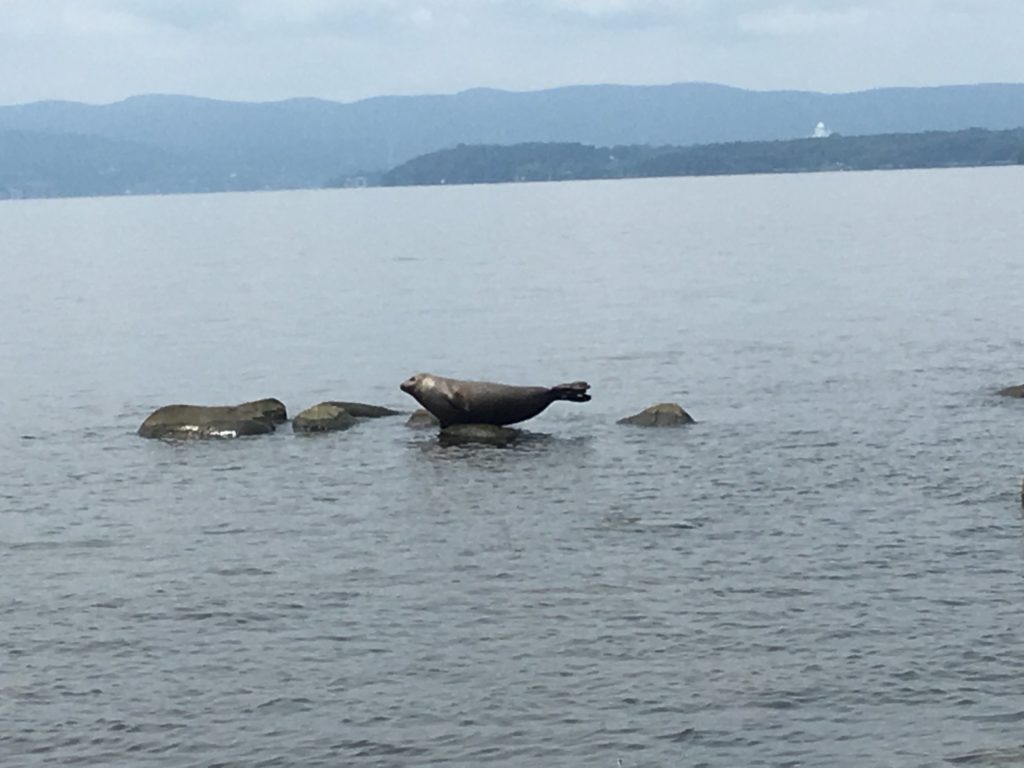

And it’s not just fish that rely on Haverstraw Bay and the entire Hudson River estuary. Far from it. A wide variety of marine mammals have also been recorded there in summer, when, as Lake puts it, “Haverstraw is like an all-night deli.”

Source: www.rewildingschool.com

In the past quarter century, four seal species (harbor, gray, hooded, and harp), three dolphins (bottlenose and Risso’s dolphin and harbor [common] porpoise), and most famously, even a minke (in 2007) and a humpback whale (in 2016) have paid visits. Perhaps most famously, a wandering Florida manatee made the river its home for a time in 2006.

During my regular walks at Croton Landing, I’ve most often thought of the waters of Haverstraw Bay—slate gray or silvery, calm or roiling—as merely part of the scene’s palette of color and movement. But now I find myself always on the lookout for a passing manatee, leaping sturgeon, or a glimpse of any of the other surprising riches the bay has to offer.

Copyright © 2020 by Joseph Wallace